Index

Back

Next

A

description of the Locomotives

There were only two locomotives owned by the Maroochy Shire Council for the

Mapleton Tramway, both small Shays of Model Abe named Dulong and Mapleton.

The Dulong was

a type A, class 13-2 loco, builder's number 2091 of 1908. The class number '13-2' simply means that the machine weighed 13 tons in working order and

had two trucks or bogies. These bogies were fitted with a gear ratio of 2.47 to 1.

This provided

a tractive effort of 6050 lbs, giving

a hauling capacity on the level of 643 tons. The Mapleton also was a type

A, class 13-2 loco, builder's number 2800 of 1914. The two locomotives were

similar in size, appearance and power, but there were differences in detail that

enable them to be readily differentiated from each other.

This

builder's photograph of the Dulong was taken just as it was being despatched from the

Lima Locomotive and Machine Company's Works on a standard gauge flatcar. It shows the locomotive fitted with a stovepipe or 'shotgun'

chimney. This was unusual for a small Shay, large spark-arresting chimneys

usually being fitted. It also shows the letters 'M.C.S.M.' (Moreton Central Sugar Mill)

painted on the bunker, but no name on the cab-sides. The agent's plates for

Gibson, Battle & Co., Ltd. are already fitted on the bunker top, so this means that those

plates were cast in the U.S.A., not in Australia. The official Lima builder's

plate is seen fixed to the smokebox.

Shay

Locomotive classes and specifications

Builder's

photograph of the Dulong before it left the U.S.A., with specifications

and other data

Builder's

photograph of the Mapleton before it left the U.S.A., with specifications

and other data

It is noted that the

information published in the above web pages does not entirely agree with some other

published data. Some variations include:

the wheel diameter of the Dulong is given as 22 inches (the standard

size), that of the Mapleton as 22.5 inches;

the gear ratio of the Dulong is given as 2.467 : 1, that of the Mapleton as

3.077 : 1;

the boiler diameter of the Dulong is given as 24.75 inches, that of the Mapleton as 27.75

inch

es;

the

working boiler pressure for both locomotives is given as 160 pounds per square

inch.

The wheelbases of the Mapleton Shays are 17 feet 6 inches,

substantially shorter than that of the standard Abe 13-2 locomotives at 18 feet

10 inches. Also, the coal capacity is about 35% more and the water tank capacity

20% less, giving a net saving in weight of about 3.6 cwt. These were probably

modifications made by Lima to make the Dulong more suitable for the

specific requirements of the Dulong Tramline, in particular the Highworth

section with its horseshoe curve. When the Shire Council was ordering the Mapleton,

they probably agreed to the same modifications for the same reasons.

A line drawing of

the second locomotive, Mapleton, by E. M. (Mike) Loveday

Mounted above the front half of the frame was the boiler, complete

with smokebox at the front end and firebox at the rear. Behind the firebox was a

wooden cab for the driver and fireman, and behind that the bunker, which had

space for coal and a water tank.

As with all Shays, the boiler was offset to the

left, to allow for the

weight of the engine

fitted to the

right

hand side. This engine, located next to the firebox,

was a

small, vertical two cylinder steam engine, which turned a longitudinal

crankshaft at axle level.

Cardan drive

shafts ran forward from the crankshaft to the front bogie and back to the rear bogie.

These shafts had universal couplings at each end, and squared slip or sleeve

joints in the centre.

Bevel gears on the rotating

shaft engaged at right angles bevelled crown wheels bolted to all the right-hand

bogie wheels with a gear ratio of between 2 and 4 to 1, depending on the

customer's requirements. These wheels were fixed to the axles as were those

on the opposite side, and adhesion of the smooth driving wheels with the rails

was relied on to drive the locomotive along. This meant that all wheels were

driving wheels. The slip

joints and universal couplings in the drive shafts enabled the bogies to swing

and tilt through curves and undulations without loss of power.

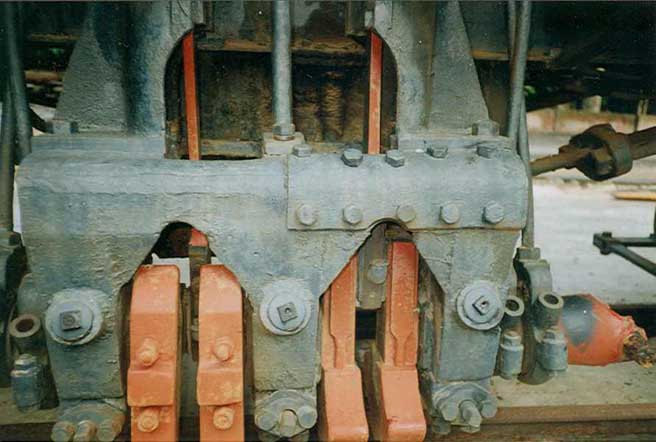

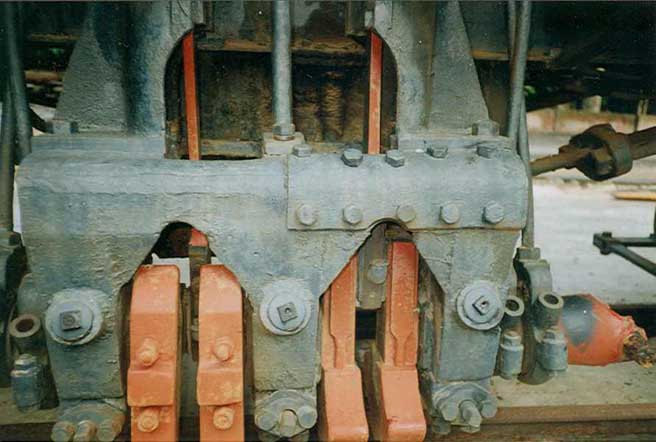

The bevel gear and

crown wheel on Shay's rear axle. Note that the pinion was not properly

meshed with the crown wheel before the key was hammered into its slot.

Because of the low gearing,

these locomotives were limited to a top speed of about 12 miles per hour (20

kph), and could cruise comfortably at about 8 mph (13 kph). Though slow, they sounded as if they were travelling much faster.

Whereas conventional steam locomotives tended to shake from side to side on a

vertical axis, due to the longitudinal thrusting of the pistons on one side,

then the other (nosing), Shays tended to rock gently on a horizontal axis, due to the

pistons working vertically. Crews regarded them as smooth and steady riders,

despite the noise and vibration caused by the gears and high engine revolutions

per minute.

When running ahead, there was a tendency for the off-centre drive

to lift the loco to the right (driver's side) if sand was applied under

slipping wheels before steam was shut off, or if an axle broke or the gearing

jammed, and to the fireman's side when running in reverse.

The gearing down of the engine

had the effect of more than doubling the tractive effort normally produced by a

loco with cylinders and wheels of that size. Also, the increased engine revolutions for a given

road speed provided a smoother application of power to the wheels. As all the

wheels were driving wheels, all the locomotive's

weight including coal and water was available to assist adhesion (the grip of the

wheels to the rails). The use of bogies meant that the locomotive avoided the

problems experienced by conventional engines with large fixed wheelbases - the

Shay could traverse indifferent track, sharp curves and sudden changes in

gradient with alacrity. In some logging operations, Shays were equipped with

large, wide wheels with flanges on both sides, and ran successfully on track made of

smoothed logs!

Conventional locomotives with

their heavy connecting rods and coupling rods need counterweights fixed in the

wheels to counterbalance the forces of the whirling rods. But, as the wheels

revolve, the counterweights deliver a 'hammer-blow'

to the track on every revolution, which in extreme cases can cause track

or bridge damage. Having no counterweights in their wheels, the Shays did not

suffer from this problem. As there was no mechanism or frame underneath the

firebox, the flow of air into the grate was not restricted, making for efficient

combustion of fuel. The engine, drive shafts, joints and gears were all easily

accessible, which made lubrication and repairs easier. All of these attributes

were advantageous to the Shay, but the downside was its low speed, high fuel

consumption and higher maintenance costs, as there were more moving parts.

Chassis details

The Mapleton Shays had a rigid steel frame or chassis made up of two longitudinal

steel girders and some steel cross members, built strong enough to support the boiler, cab, bunker and

drawgear. This frame was 22 feet 8 inches long, and rode on the two bogies,

which swivelled on pivots front and

rear. Each bogie was of the Archbar type, and was fabricated from steel bar with castings for bearings

etc. bolted on. The bogies had four wheels, all of the same diameter, on a 4 feet wheelbase.

At

each end of the locomotives were substantial timber buffer beams, to which the drawgear was attached.

On Dulong this took the form of three coupler pockets, mounted one above the other and cast as a

single unit. This was to enable coupling with wagons whose couplers were of different heights

above the rail. The Mapleton had a single round bumper fixed to the lowest part of the buffer beam.

The

boiler and fittings

The boilers of the Shays were very small, being less

than 2 feet 6 inches in diameter and only 9 feet 4 inches long (excluding the firebox and

smokebox). To produce enough power, it has been claimed that the boilers had to be run at 200 pounds per

square inch of steam pressure, higher than most conventional locomotives of the

time. Even some contemporaneous full-sized Australian express passenger

locomotives did not operate at such a high pressure, e.g. the B17 on the QR at 175 pounds per

square inch, and the NN on the NSWGR at 180 pounds per square inch. Also, the Shay

Catalogue states that all Abe class locomotives left the factory with the safety

valves set to open at a pressure of 160 pounds per square inch. All Shay

boilers of that vintage produced saturated steam, as superheating had not yet come into vogue.

The boiler was rigidly bolted to the frame at the

firebox end. This meant that as the boiler heated up, it expanded towards the

front of the locomotive, and the smokebox end moved forward.

A steel arm was attached to each side of the smokebox and pivoted on

trunnion joints

to the chassis underneath, to hold the boiler more or less level as it expanded forward and

contracted back. This arrangement was necessary because the engine components were

fixed both to the firebox and the frame, and these items had to operate together

as a rigid unit. Conventional locomotives have the smokebox fixed to the frame

in a saddle,

and the engine cylinders are fixed to it. This means that the rear of the boiler

moves back into the cab as it expands, and needs to be supported on sliding bearings, usually located on the sides of the firebox.

Mounted on top of the smokebox was a chimney fitted with

a large spark arrestor.

These were used because

coal-burning locomotives had a tendency to throw sparks from their chimneys when

working hard, which could lead to fires starting in the grass and canefields

along the tramline. These spark arrestors came in various designs, and

gave each locomotive a distinctive appearance.

When

the Dulong was purchased, it had a stovepipe chimney (see photograph at

top of page). Upon arrival in Nambour it was

fitted with a diamond spark arrestor which had a top section larger than the

bottom section. See Section 13

for details and photographs. Then the loco had its 'sensational tramway

accident' three years later in which the chimney was destroyed - see Section

15. A conical spark arrestor similar to that on the Moreton was

fabricated at the Mill and fitted to the Dulong's smokebox.

There are at least three different types of spark

arrestor shown in photographs of the two Shays, and other minor chimney

differences as well. Two types of diamond-shaped arrestor are seen, one whose

top section is larger than the bottom, and one whose bottom section is larger

than the top. Some photographs also show a lip at the top of the spark arrestor.

Dulong, before its

accident.

Mapleton, when new

One type of conical spark arrestor is seen, which is identical to that on the

preserved locomotive Shay. It is not known how long the chimneys lasted and if they ever

burned out and needed to be replaced, but this is fairly likely. The spark

arrestors contained baffles and screens, which probably also needed periodic

replacement.

Generally

speaking, between 1911 and 1948 the Dulong was the loco fitted with the

conical spark arrestor, but the photograph below shows the Mapleton,

quite new as it still has its headlight and bell, having been temporarily fitted with this chimney, apparently as an experiment.

One

thing is for certain, the conical spark arrestor is possibly the ugliest fitting

ever placed on a steam engine, and it continues to spoil the appearance of the preserved

locomotive today:

Three sand boxes were carried on the locos to provide a

supply of sand to assist adhesion of the wheels to the rails. One was in the

form of a dome mounted on the top of the boiler just behind the chimney, in the

manner of mainline QR locomotives. Vertical pipes led down the outside of the

boiler from each side of the sand dome. These pipes terminated near each rail

top just ahead of the rear wheelset of the front bogie, to provide sand for

forward running. The other two boxes were located on the back of the bunker, one

for each rail (see left picture of Dulong above), and provided sand for running in reverse. Blockage of sand in a

single pipe led to increased friction on one side of the locomotive only, and

this sometimes caused broken axles. Both locomotives had a 21/2

inch wide strap placed around the sand dome near its base.

A second dome casing between the sand dome and the cab contained a raised

steam dome built into the top of the boiler. On its top were mounted the safety

valves and whistle. The dome was raised so that dry saturated high-pressure steam could be

collected there, away from the turbulent boiling water level. The steam then

travelled under pressure through an external "dry pipe" to the driver's

regulator valve, and from there to the cylinders. The Dulong's steam dome was

taller than the sand dome, and about the same diameter. That on the Mapleton

was the same height as the sand dome, but slightly fatter. This is a key clue to

correct

identification of the locomotives.

The two

Shays at the Mapleton water tank - Dulong on the left, Mapleton at

right.

The photograph below also shows the Mapleton and Dulong

at the elevated water tank at Mapleton Station. Maintenance is in progress

on Mapleton. What is interesting about this picture is that the

boiler-mounted sand box has been removed from the locomotive completely, quite a

task for men with only rudimentary workshop facilities. The steam dome also has

its cladding and top cover removed, indicating that access needed to be gained

to the interior of the boiler.

The rebuilt locomotive Shay

seen below has

the Mapleton's boiler with the short, fat steam dome, and probably the

Mapleton's sand dome, but it has the Dulong's conical chimney.

The steam went backwards from the side of the steam dome in an external

"dry pipe" pipe on the right-hand (driver's) side, to the regulator in the cab. From

there it went to the engine, which was rigidly bolted to the right side of the firebox,

impinging into the cab. Entering the two steam chests, one for each cylinder,

the steam was admitted to the cylinders through slide valves operated by

Stephenson's link valve gear.

Exhaust steam travelled forwards through a second

external pipe sloping down as it went forward from the top of the cylinders to

the footplate. This pipe entered the bottom of the smokebox just above the front

bogie, and terminated in a blast pipe located directly under the chimney. The

used steam was therefore exhausted up the chimney in the usual way, the blast

causing a reduction in pressure in the smokebox to provide a draught on the

fire, and producing the puffing sound characteristic of a steam engine. Towards

the end of their time as Shire Council locomotives, both engines had their

smokeboxes extended.

The spark arrestors tended to restrict the blast and

muffle the exhaust sound of the locomotives, and this combined with the rapid exhaust beat (due to the

gearing) to give the impression that the locos were not working hard, even at

full cut-off.

Each locomotive arrived with a brass bell in a bracket

on the boiler top, fitted between the two domes. These were a feature of

American locomotives, but were soon removed.

Acetylene headlights also were

supplied, but these were later replaced by battery-powered electric lamps. From

the early 1930s, there were no headlights at all, even the brackets having been

taken off.

For a time during the 1920s, both Shays had a handrail

running along each side of the boiler and around the front of the smokebox.

Engine and

transmission

The

engine was a vertical two cylinder type, with pistons having a 152 mm (6 inch) diameter and 254 (10 inch)

stroke. In layout it was like a marine engine, except that both cylinders were

identical and simple expansion of steam employed. It was built up using a number of castings, and bolted

to the firebox. Beneath the cylinders was a longitudinal

crankshaft which converted the up-and-down motion of the pistons and crossheads

to rotary movement, through a connecting rod attached to each crosshead and

piston rod.

The engine unit of Shay

in 2006, with the drive shafts removed, prior to transport to Ipswich

Railway Workshops..

In forward gear, the crankshaft rotated in an anti-clockwise

direction as viewed from the rear of the locomotive. The Stephenson's valve gear

controlled each valve by a link moved by two eccentrics running on the

crankshaft. The choice of forward and reverse gear, and the amount of cut-off

applied to the valve events, was controlled by the driver using a conventional reversing lever (Johnson bar)

in the cab. Cylinder and valve chest lubrication was through oil introduced to

the steam flow as an emulsion, also adjusted

by the driver as one of his duties.

Shay's crankshaft in

2006, with the drive shafts removed.

At the front end of the

crankshaft a universal joint was fitted. This transmitted the power to a shaft

which ran forward to another universal joint mounted just behind the rear axle

of the front bogie, which brought the engine's torque to the bogie itself.. This shaft would need to lengthen and shorten as the bogies

turned through corners. It was therefore made in two pieces of square-sectioned

steel, one piece being solid, and the other a hollow sleeve, but of a larger

cross-section so that the solid section could slip inside it as a sliding fit.

The square section ensured that if one shaft turned, the other would also. This

slip joint enabled the shaft to lengthen and shorten while still transmitting

power.

The universal joint on the

bogie was at the rear end of a solid shaft which ran forward on the right-hand

side of the bogie to a point forward of the front axle. This shaft ran in

bearings that were in the same castings as the axle boxes, so that the shaft was

exactly level with the wheel centres. Just forward of each axlebox, a bevel gear

was fitted, which meshed with crown wheels bolted to the outside of each of the right-hand

bogie wheels. The bogies themselves had

four wheels, all fixed to their respective axles.

The rotating

crankshaft thus had its torque transmitted through the universal joints and slip

joint to the bogie drive shaft, which turned the four bogie wheels through the

bevel gears, crown wheels and fixed axles.

A similar combination of

universal joints and slip or sliding joints ran back from the crankshaft to the

rear bogie, which also was fitted with bevel gears and crown wheels. This mechanism enabled torque from the crankshaft to be transmitted

to both bogies as they swung to right and left around corners, and tilted up and

down on gradients or undulations in the track. A photograph above illustrating

the gears on the back axle of the second bogie is repeated below

for convenience.

There were limits as to how

much swinging or tilting these shafts could accommodate. On the Image Flat

Branch, there was one curve where driver Bill English Jnr claimed it was so

tight that the universal

joints would knock. This was probably at a kink in the curve, as it does not seem

to have been particularly sharp otherwise. When derailments occurred, it was

possible that the bogies could rotate beyond their designed limits, resulting in

the solid part of a slip joint dropping out of its sleeve, as in the

photograph below.

Mapleton in trouble - the loco has

split the points, the front bogie turning while the rear one goes straight

ahead. The driver looks as if he is trying to reverse, but this attempt is probably ill-advised,

as the slip joints taking power to the rear bogie have become disconnected, and the universal joints

leading to the front bogie appear to be outside their designed working limits.

The engine was mounted on

the firebox at a height that would place the centre of the crankshaft's rotation

at the same height above the railhead as the bogie axle centres. This would

place all gears, drive shafts, slip joints and the crankshaft in a horizontal

line, which was preferable for smooth operation. Some photographs, though, show

misalignment in the tramsmission devices, usually the crankshaft appearing

slightly lower than it should be. This would be caused by modifications made to

the bogie mountings, and in fact the top bars on the bogies, originally arched

upwards, were altered to the horizontal, as they still are on the preserved Shay

today.

The braking

system

Both Shays had a steam

brake in which the driver's brake valve admitted live steam to a cylinder under

the cab floor on the fireman's side. This operated linkages that pressed brake

shoes against all the locomotive's wheels. There was also a hand brake, operated by a crank on a vertical shaft just ahead of the bunker,

within easy reach of the fireman. This was supplied as a parking brake, but was often used when

running as well. There were no air brakes nor vacuum brakes. A serious accident in 1934 was attributed to failure of the steam brake.

The cab and bunker

The cab was completely built of timber, with a curved

roof. Hinged windows on the cab front allowed both members of the crew to have ventilation if

required. Glass windows were fitted to the cab sides, and the Mapleton had

windows in the panels at the back of the cab. After the accidents to each loco,

the cabs were repaired to the original design. Behind the cab was a steel bunker, able to carry 13.4

cwt of coal on top of a water tank with a capacity of 320 gallons. The coal was

carried loose or in sacks.

When it was purchased by the Moreton Central Sugar Mill, the

Dulong arrived with 'MCSM' painted on each side of the bunker. At Nambour, the name 'Dulong' was

soon painted on the cabside below the window. Not long after, the 'MCSM' was

removed and the name 'Dulong' painted on the bunker sides. The cabside was left

blank. The Mapleton arrived with 'Maroochy Shire' painted on the bunker

sides. This was soon removed and the loco left unadorned.

Both

Shays were obtained from the Engineering Supply Company of Australia (ESCA), who

arranged the order through Lima's Australian agents, Gibson, Battle & Co. of Sydney. As well as the standard Lima builder's

plates mounted on each side of the smokebox just above the footplate, the

locomotives were delivered with large agent's plates mounted high on each

bunker side. These plates were 24 in. long by 91/2

in. wide, and may be discerned in some photographs of the

Dulong and the Mapleton. A photograph of Dulong

hauling logs shows the holes in the left-hand side of the bunker which had

been used to secure the plate, which is missing. The agent's plate below is now held

in the care of Mr Clive Plater, of Eudlo.

The Mapleton on an early excursion. The bell, handrails, two

headlights and brackets, builder's plate on smokebox, Shay patent plate on

lower cabside and Gibson Battle's agent plate on bunker are still

in position. The bell was sold to the Mapleton State School in 1923.

Index

Back

Top

Next